LeGrand Jacob, G., 1860, Extracts from a journal kept during a tour made in 1851 through Kutch, giving some account of the Alum Mines of Murrh, and of changes effected in 1844* by a series of Earthquakes, that appear hitherto to have escaped notice. Trans. Bombay Geog. Soc., 25, (May 1858-May 1860), 56-66.

* [note: he means 1845]

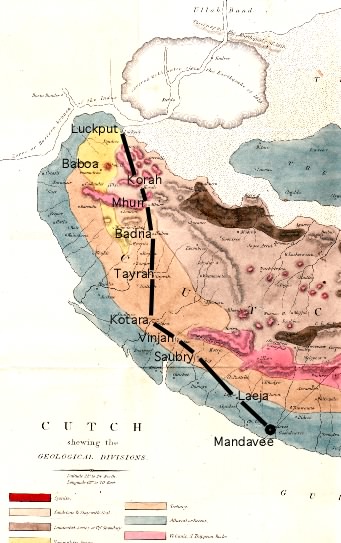

Read before the Society Feb 20 1862. (The map above is from Grant 1838 (click to enlarge). and each town is spelled differently from those below e.g. Tera=Tayrah).

Mandavee, Monday 10 Nov 1851 05:30; Left Mandavee and reached tents at Bait 08:45. Shahaboodeen with perambulator, makes the distances thus.

My bungalow to Mandavee Walls |

3.36 km |

Seerwa (or Sherwa) |

6.63 km |

Baeewala Waree |

4.22 km |

Laeja (a small walled town of the Jaraja Bhajad) |

6.6 km |

Total to Bait |

25.5 km |

A level country all the way, dry, burnt up and occasionally sandy; the monsoon crops stunted or failed from want of the latter rain; hardly a tree to be seen save near villages; the country looks under a curse. Bait is a Darbar village; no shelter for tents; but there are some good trees in the village. The tank abounds with wild duck. Aneroid lower by 60, thermometer 88°F at 3 pm in tent.

Tera, Tuesday 11 Nov 1851.Tera is spelled Tayrah in Grant's map of 1837 above.

Left Bait at 05:00. Temperature inside tent 63°F, outside 60°F.

To Dedia |

7.24 km |

Sabraee |

3.51 km |

Halapoor |

0.93 km |

Kotharia |

4.44 km |

Wundee |

4.46 km |

Winjan |

4.02 km |

Total |

24.82 km |

I should have guessed it nearer 18 miles: during the journey two broad and tolerably deep monsoon rivers; Aneroid lower here by 65, thermometer at noon 94ľ - hot, dry, dusty, no shade for tents, - reached them at 9 am, the country parched up and treeless. Soil level and sandy, especially for the last two miles, but the cultivation improves on nearing Winjan, the crops chiefly cotton and moong, but also some bajree, juwaree, guwar, til, and castor-oil, that seem more or less to have survived the drought, - the bajree reaped; for the first half of the road, however, the country most desolate.

There would appear gradual ascent as the Aneroid continues slightly to fall. Atmosphere exceedingly dry, sun parching hot, thermometer at noon 93°F, up to 1pm to 94°F and then falling to 93°F till 3pm, when it gradually lowered.

This is a Bhayad town belonging to Jareja Sahebjee, and the Koover Dewajee came out to meet me. It is not a nice halting place, being dusty, without shelter, the town in ruins, the water bad – they drink the foul water of the tank. A deep and broad monsoon river passes close south side of town.

These Native gentry seem effete and dying out, even the most benevolent policy can scarce maintain them for another century in existence. Is it that the robuster northern race cannot keep up its breed here, as with the Momlooks in Egypt, or is it from sensuality in youth, or from both united? Nature seems almost to have set bounds to certain races as of yore to the Pletheosauri, etc. etc. This is a lovely country for the geologist, but for little else.

Tera, Wednesday 12 November 1851. Tera Left Winjan at 5:15, arrived here 10:30 am, - delayed on the road by bustard and duck. This is a considerable town recently obtained by the Darbar from Jareja Somrajee, about which transaction so fierce a battle has been waged. The Rao have built two Martello towers, etc: the old bastions and walls were mostly thrown down by the earthquake of A.D. 1819, the debris still lying about: two small lakes close to the town, separated from each other by the roadway embankment, with some good-sized trees, give the place a cheerful appearance, the more enjoyable after the desolate country traveled through.Distances:-

Winjan to 1st Wara |

3.97 km |

to 2nd Wara |

3.62 km |

Kaoora River |

2.83 km |

Bachoonda |

2.19 km |

Konathee |

6.71 km |

Tera |

4.98 km |

Total |

24.3 km |

Tera, Thursday, 13th November. – Halted here for the interview with Jareja Somrajee and Bhayad. A tedious repetition of arguments and reasoning, something like speaking to a rock and getting back echoes.

Badra, Friday, 14th November. – After all the reports of the fierce tusker, disappointed at finding nothing but small game: however ‘tis a consolation that the ground is bad – full of deep nullas, and ravines, and standing kirbee. Distances –

Tera to Chupree River |

3.82 km |

Bhalapoor (S.Bank of Badra R.) |

13.3 km |

Badra on north bank |

1.28 km |

Total, Tera to Badra |

18.4 km |

Thermometer at 5am, 76°F, 3:30pm 91°F. Aneroid continues falling between 6 and 7am; a sharp thunderstorm to northward; much forked lightening; black clouds and slight rain; double rainbow.

Murh Saturday, 15th November. – Mudh, or more commonly written as well as pronounced Murh. Thermometer on leaving Badra 6am, 70°F in, and 68°F outside of tent: at 3:30 pm 91°F. Aneroid continues falling.

No village on the road but a few small and one middling size tank: the last well supplied with wild duck and geese. Distances –

To Gopalwala Talao |

4.27 km |

Murh |

7.05 km |

Total, Badra to Murh |

11.3 km |

This place is celebrated for its Alum works – the manufactory a royalty; the village belongs to the priest of its Mata temple, a shrine much honoured by the Rao. Substances are found here in the soil that burn with a scent, something like frankincense, called Bhootkana and …..(*left blank in original and now forgotten, the specimens are unfortunately mislaid). Visited, in the evening, the Alum mines with the head man, a Mahomedan, who has retained their management by his family for 5 or 6 generations: all his workmen, he told me, are Mahomedans. The soil is excavated by narrow shafts dug at an acute angle downwards, penetrating afterwards by arched pathways, branching off with numerous ramifications into the substance of the earth, which is removed as basis of the manufacture: heaps of this soil are piled up at the mouths of the shafts. I descended by torchlight, and after winding about at a depth of about a hundred feet from the surface, for a few hundred paces hither and thither, cam again into daylight at about 150 yards from the spot where I entered: the soil was soft and crumbling, yet only one fatal accident by falling in of the earth was know to have occurred, it tasted like salt mixed with ashes.

The next process is to remove this earth to the drying pans (like those of a common salt-work), where it is thrice saturated with water during nine days, the residium cakes after drying, when it is taken up and thrown into huge cauldrons and boiled together with one fourth its quantity of saltpetre. After cooling, the substance is washed with water from the reservoir, near a temple, of brackish water, to which superstitious qualities are attributed, and then again boiled and poured into frail earthen vessels, where it is left to dry: this is the last stage of the manufacture; the pots are broken and the alum either exported in lumps or crystals as the state of the market may require.

The workmen dig the soil, furnish the saltpetre and manufacture the alum from first to last at their own expense, receiving two korees the maund for their labour; from forty to fifty thousand maunds are yearly made, they told me, though at present the works are at a standstill, owing to the difficulty of finding a market at remunerating rates. The whole of the manufacture is a royalty, and the sale managed by the Rao who keeps a couple of horsemen and a dozen footmen at the place to watch: and assist: only a portion of the saltpeter required is produced here, the rest comes from other quarters: the mines have been worked, they tell me, for five or six centuries.

The town contains between four and five hundred houses and has a dirty, dusty, parched up appearance: the heat in summer must, I should think, be great. The village is held in grant by a Gossaeen of the Mata temple, which goddess is supposed to have a good deal to do with the product. The temple is a common Hindu one; the only things I noted were, a stone tiger facing the sanctum, as her goddess-ship’s wahun (riding steed, vehicle of transport); a couple of Gossaeen covered with ashes and ochre sitting cheek-by-jowl with the tiger.

Gave Mookundjee and Krishnajee Punt leave to make a pilgrimage to Narain Eshwar, a shrine on the sea-coast, near Koteshwar (the port of Lukput), held in great repute. A yesterday’s track of a large boar taken up from Gopalwala talao gives my puggees hope of showing me sport, but ‘tis a very difficult riding country’. Murh is situated where the Abrassa ridge appears to terminate, throwing off a confused mass of spurs.

Kora, Sunday, 16th November 1851. – A small village and Dak station, as the road here joins the main line from Bhooj to Lukput. Thermometer at 6am inside tent 70°F, outside 67°F. The Abrassa ridge does not terminate at Murh as I guessed, but continues only in a more northerly direction, throwing off a spur just above Murh to the westward. On ascending the tower close to the village one perceives that Murh must stand near the centre of the volcanic upheaving force.

What a mysterious thing is natural religion. In the midst of their barbarianism, these Hindoos seem always to possess taste and discrimination in the selection of sites for their temples, dedicated to the supposed Deities of nature. Will there arise any one at any time to clear up these mysteries? One seeks in vain for a clue in our own religion, which limits itself to itself, and reason is a poor torch to enlighten us on things beyond the region of our senses. Two temples here gave birth to these thoughts – one over a natural spring in a sheltered nook, the other on the hill-top. No village between Murh and this, but three small tanks, distance, 13.2 km.

Lukput, Monday, 17th November 1851. – Thermometer at Kora inside tent at 4:30 am, 60°F; outside 53°F; so cold weather has set in again.

Distance measured hither as follows:-

Kora to Kaleewaee R. |

4.83 km |

Dha (Darasee) |

1.83 km |

Oomursur |

7.42 km |

Lukput fort |

9.88 km |

Total Kora to Lukput |

24.1 km |

Total Mandavee to Lukput |

142 km |

This has been an uninteresting ride: the Abrassa ridge continues irregularly till near Lukput, and is terminated by small hillocks having all the appearance of intense volcanic action – scarcely anywhere a blade of grass to be seen. There must be sportsmen here, for the deer are very wild. The Kamdar came out to meet me – a Brahmin, yet dressed and bearded like a Rajpoot, and speaking Persian like a Mussulman; an intelligent man, of pleasing manners; he had accompanied Burnes to Sind: repeated several of his sayings, and spoke highly of him.

Lukput, Tuesday, 18th November. – Halted here today. Rode to the Bunder, and chatted with the boatmen. I now record information collected, and the results of observation yesterday and this morning.

The ramparts of the town completely encircling it are lofty, nearly three miles round, with parapet of about seven feet, banquette about six; numerous bastions, some boasting a cannon, all loop-holed for musketry and in good order; the ditch narrow, shallow and dry. The sea approaches within a few feet of the ramparts at spring tides.

The town is desolate; the greater part of the houses deserted, and many fallen down. The traders have quitted for Kurrachee, Bombay, Mandavee, and other ports. This ruin is attributed to the conquest of Sind by the British, whereby the duties on goods have amounted to prohibition; in the time of the Ameers this was one of the chief ports for the Sindian trade.

On traversing the town this morning from South to North, I counted, gateways included, twelve human beings. The only signs of life were two men engaged in making a cart.

The Runn hugs the northern ramparts at about ¾ of a mile from which the creek cuts through it, bending round to the bunder about 11/2 mile N.E. of the town; here reside all the maritime population in a dozen miserable huts, the remnant they say of nearly two hundred in olden times. A cartway has been made from town to bunder of earth raised some couple of feet, but ‘tis crumbling away. The Runn is sufficiently hard to allow traffic on either side of the roadway, but in high tides the sea covers all but the raised cartway: the port, if I may dignify with such a name a fisherman’s hamlet, huts and a few small craft, is only protected from these high tides by a low mud embankment. Wood and water have to be brought from the town. Some dozen seamen who told me they lived there all the year round, crowded round me. Their headman, whom they called jemadar, although a Mussulman, could neither speak Gujarathee nor Hindoostanee, his language was a mixed jargon of Sindee, Kutchee and a little Gujaratee, but some of the boatmen could speak intelligibly and one was exceedingly intelligent. The Bundur population they said was formerly …… was now reduced to a score: they complained of being half-starved, and they looked it; they had no clothing to keep them warm during the cold season. Three years ago the Rao came here and fixed the toll for passengers ferried over to Sind, on which side they live, but so badly as seriously to contemplate migration. The charge is a koree per head. The only place they cross to is a building called Kotree, some six miles off in a northerly direction: through the telescope it looks like an upper-roomed cottage. Here a Brahmin resides from religious motives to bestow water on all travellers: the water is kept in a wooden tank and in vessels, each ferry-boat taking a small supply. The Rao pays for this as a charitable grant. From that lone and desolate cottage the Runn extends 8 kos in the Kurrachee direction, and 14 towards Hyderabad, without a vestige of life. Either distance is generally traversed by a forced march at night time; not a drop of water is to be had by the way. Camels, cattle, etc. cross the creek at low tide, and are obliged to make a circuit of 6 or 7 kos, owing to the mud, to get to Kotree, and at the best have a troublesome time of it.

They tell me that at high spring-tides there is three fathoms of water opposite Sindree, 16 kos from this, but that some intermediate spots are so shallow, that it was doubtful whether the ferry-boat or Sind Dhoudee, capable of carrying 30 persons, could go through even then. These boats are flat-bottomed and draw a cubit (1½ foot) water. As is well known, Sindree was sunk by the earthquake of A.D. 1819: its bastions are still visible and left standing here and there, but the place is utterly desolate. The inhabitants effected their escape in boats. The water up there is so salt, that fish are not to be found, except a few during the monsoon.

The tide rises here 4 ½ feet usually, and 9 to 10 feet at the springs. At the Bundur they said there was a fathom and a half: the surface of the water was only three feet from the level of the Runn, the soil of which is here as tenacious as clay: there is no sloping bank. The creek has cut its way through, leaving perpendicular sides ready, apparently, to fall in at the caprice of every tide.

One of the men stood before me on the spot some hundreds of yards away, where they informed me, only 12 years ago the creek ran with 3 fathoms of water, whereas it has now dwindled down to half and formed a new channel: the level surface does not betoken any such change.

All would be saved, they said, if the Meer’s Bund were thrown open, as the Indus would then force itself a clear path down as in former times.

The only sign of trade visible was a few heaps of small brick-colored stone called Geroo, a kind of ochre, obtained near this, used for dye, the Rao’s duty on which is two pice per maund. A yellow stone called Kaya, is also, they say, exported for dye. Seven or eight Hindoos were here, returning to Sind from a pilgrimage, and waiting to be ferried across; these men and the stones were the only symptoms of traffic visible. This bunder does not admit vessels above 30 khundees, and that only at spring-tides.

The sea-port of Lukput is Koteshwar, curtailed to Kotesur, 9 kos distance, which admits vessels of a hundred khundees; but the roadstead is rocky and unsheltered. I am further informed by my people, who have just returned from that quarter, that there were only 5 or 6 vessels then lying there, and none above sixty khundees.

Old Mookundjee, who was here 52 years ago, then a lad of seven, says he has a clear recollection of the creek being the 5 or 6 kos broad, whereas it has now shrunk to less than a mile*(footnote: “Considering his youth this must be received with caution: information others collected points to diminution in depth than in width”): high spring-tides however, would make a great difference by spreading over the level Runn.

Mookundjee says that at that time Futteh Mahomed was building the Lukput fort and the Ameers of Sind sent word, that unless this was discontinued, they would cut off the supply of water, and thereupon commenced the building the Alee Bund; Futteh Mahomed treating their threats lightly, continued his work, boasting that when this was finished, he would at any time open the Bund with a few pick-axes: the anarchy ensuing in Kutch defeated his intentions on Sind.

Spent all the afternoon with my tent filled by the best informed men of town and port, assembled for me by the karbharee before alluded to, as having been with Burnes in Sind etc., an intelligent man, himself giving information, and helping to get it for me from others.

One of the Rao’s garrison in Sindree at the time of its destruction in A.D. 1819 was also present. The following is an abstract of the notes made after much examination and cross-examination.

The Ameer’s embankment is called Alee Bundar Bund and the Meer’s Bund, but it is not the only one. Meer Thara was one of the five Talpoor conquerors of the Kaloras, who received Meerpoor as his portion; he was the father of Alee Moorad, and named the bund after his son. This bund is 10 kos above Sindree. The Talpoors fled into Kutch from the Kaloras in Sumvut 1813 (A.D. 1786-87); resided at Moondhan for six months and then returned to wrest Sind from their rivals. Futteh Mahomed began the Lukput fortification in Sumvut 1852 (A.D. 1795-96), and completed them in Sumvut 1857 (A.D. 1800-01). Hemraj Raojee, aged 74, remembers drinking the creek water during four months of each year up to Sumvut 1857, viz. in Ashdah, Shrawun, Bhadurva, and Asoo, hence the fort and the bund would appear to have been completed together 51 years ago.

The creek was then 10 to 12 fathoms deep, and native craft of the largest size frequented the port: the breadth of this deep stream was a mile and upwards: the cattle of Lukput were fed from the hay cut from the opposite coast, where now not a blade of grass is to be seen for a day’s march. This supply of fodder ceased in or after Sumvat 1861 (A.D. 1804-5).

The Alee Bund is described by one who saw it four years ago, as one hundred yards long, twenty-five broad, and four high, above it the water sweet, and waist high, below only driblets or dry: during the monsoon the water below is salt.

About 13 years ago a Suyud in service of the Sind Government, finding some water escape from the Alee Bund, raised a small one lower down in mid channel about 3 yards high, sufficient to dam up the overflow of the higher embankment: this is called the Suyudwalla Bund.* (footnote: “My notes here are obscure from diverse or ill-understood testimony, and I have some doubt as to the position of this Bund.”)

But it is not to men alone that the ruin of this part of Kutch is to be traced; Providence has also directly contributed to bring it about by alteration of the earth’s level.

The earthquake of Sumvut 1875 (A.D. 1819) that submerged Sindree, elevated the bed of the river to the height of 2 or 3 yards for the distance of 2 to 3 kos, commencing to about 2 kos above Sindree: the spot is called Ullah Bund (God’s embankment)*, but the monsoon has worn a water-way through it in an irregular channel; the material being clay, sand, and gravel, this would soon be deepened and widened by any flow of water; the earth was also raised at a place called Sunda* (footnote: “Several speaking at once the subject needs further inquiry. On these two points my notes imply doubt.”) The usual tide only reaches this Sunda, the spring-tide now goes over it by a cubit, the earthquake of 1819 raised the ground as to leave the tide there waist high, but in Sumvut 1901 (A.D. 1844 [note: he means 1845]) a series of shocks occurred, that raised the earth still more, so as to leave a cubit (foot and a half) as the greatest depth of water ever found there: these shocks also extended the breadth of the Ullah Bund to the extent of 3 kos: before they occurred the usual tide went over the Sunda by about half a foot, but now not at all. At spring-tides, however, a boat drawing a cubit water can with some labour be taken over the Sunda.

The earthquakes of 1844 [note: he means 1845] here referred to I do not remember ever reading or hearing of, yet they are shown to have effected an important change in the earth’s surface: the shocks are said to have lasted during a whole month (all Jeth, Sumvut 1901), and were so threatening that whilst they lasted the inhabitants feared to sleep in their houses.

Pursuing the upward course of the river it is thus described:-

After passing the Sunda, a pool (Chuch) is reached called Mulhar, where the water I waist high at all times; this is half a kos long: then comes the Ibrahim Shah Peer flag-station, where there is nine feet of water or more, which continues past Sindree until the Ullah Bund, so that there is only the dry bed of the old river until we reach the Chuch, called the Bundrejo Duryao some three kos higher up, where the water is waist high and salt: it lasts for 1 kos, and is terminated by the Suyudwalla Bund above described.

The Banians complain bitterly of the ruin entailed on them by the heavy taxes of the new Sind Government. Before the British conquest, Lukput was a great port for the introduction of goods into Sind: now, besides 3.5% ad valorem paid in Bombay on goods brought to Kutch, these same goods are again charged 10% when conveyed across, besides such interference and annoyance at the frontier as to the amount to total prohibition.

One thousand houses of Banians, traders and those dependent on them, have been deserted since the Company took Sind. There were previously 250 Sindian merchants here – now not one.

The desolate appearance of the town corroborates the assertions of these men, but I suspect that Lukput has been on the wane ever since the alterations effected by Divine and human agency in the bed of the river.

N.B. – My tents were pitched under a large Wur tree in a garden south-west of the town.

Thermometer on the 18th at 6 am 62°F both inside and out.

18th November 1851, Lukput.